Adventure Capitalist Part 1: Zipline

Reflections on scaling Zipline from 70K to 1.5M drone deliveries across frontier markets

I recently stepped down from my role as a vice president at Zipline in order to begin a new adventure as a startup founder.

Building out the sales and business operations functions for frontier markets at Zipline was an insanely challenging and deeply rewarding experience, given the sheer ambition of the project, and the extremely high bar for execution, so I thought it was worthwhile sharing some reflections.

I worked at Zipline for 3+ years (2021 - 2024), and looking back, this was the beginning of our hyper-growth phase; we scaled from 70,000 global drone deliveries when I joined to over 1.5 million deliveries when I left. Many things were constantly breaking during this period, and we successfully pulled off a redesign of the entire drone from the ground-up for the launch of “Platform 2”, our short-range vertical take-off and landing vehicle, which is operational in the United States as of early 2025. Our “Platform 1” drone, a long-range fixed-wing vehicle, has been operational across Africa since 2016.

Zipline is headquartered in San Francisco, yet for the first 5 years of the company’s existence the majority of commercial flights took place in Rwanda. One reason for this is regulatory: the European Union Aviation Safety Agency developed a prototype performance-based regulatory framework for unmanned aircraft in 2016. The Government of Rwanda adapted this prototype framework and leapfrogged the EU in its implementation, with Rwanda becoming the first country globally to implement performance-based drone flight regulations in early 2018. Rather than a blanket rule for all drone flights, the government specifies different safety standards based on the mission that the drone is completing. This created a unique opportunity for Zipline to begin operating at significant commercial scale in Rwanda before any other market because of the sophistication of Rwanda’s regulatory environment for unmanned aircraft.

We also pitched several governments across East Africa, Latin America and South Asia on the potential of Zipline’s technology to revolutionise medical care, and Rwanda was the first country that committed to a large scale implementation. This speaks to the strength of President Kagame’s leadership team; Kagame has the vision and executional ability of a startup entrepreneur, applied to nation-state building. The Government of Rwanda was extremely early to recognise the potential of drone delivery to solve critical societal problems, such as maternal mortality from postpartum haemorrhage, and created a regulatory environment in Rwanda that enabled Zipline to flourish.

In 2023, Zipline was the first company to receive approval from the Federal Aviation Authority to conduct flights in the United States beyond visual line of sight, using an onboard perception system. Our track record of 1 million+ drone flights across Africa with zero safety incidents was a critical input to the FAA’s decision.

Building New Products

The core of my work at Zipline was conceptualising and implementing new commercial opportunities for drone delivery. My team launched several new product categories, including consumer goods, animal health, therapeutic milk products to treat severe malnutrition, and human vaccine deliveries for local health posts. Many of the ideas we had for new product categories that could be delivered by drone were complete flops, but a few projects achieved very significant scale.

One interesting example was the success of our animal health and agriculture business unit. Our CEO believed that the agriculture and livestock sector could be a large opportunity for Zipline (at the time, the company was solely focused on the delivery of blood and human pharmaceuticals). To begin with, we narrowed down on artificial insemination of pigs as the specific use case for drone delivery within agriculture that would likely be easiest to scale first for a few reasons.

Pig semen can’t be cryopreserved and must be stored so temperature and storage conditions are very important in transit.

The value per package is relatively high and pigs are in heat for ~24 hours, so semen is required on-demand.

The Government of Rwanda was very interested in transitioning the country to artificial insemination of livestock in order to improve meat yields, and thereby eliminate severe child malnutrition.

After weeks of testing the impact of drone flights on semen motility, we eventually found success with specific packaging methods. Over the next one year, we expanded pig semen deliveries across Rwanda, before launching cattle semen and livestock vaccines. The strategic insight is that we often started a new delivery category with a niche product and a customer with a very strong pain point. Once the niche product category was saturated, we then expanded to adjacent products in the same sector (e.g. pig semen + cattle semen + livestock vaccines = general animal health offering).

Growing a new program to a handful of deliveries was often relatively straightforward - the challenge came in figuring out how to efficiently scale a new use case to 100K+ deliveries in a resource constrained environment, while maintaining a perfect safety record. In an environment like Zipline, you have to figure out what fires you should let burn, and what fires pose a serious risk of burning down the entire company. You cannot solve every problem, and you must prioritise ruthlessly in order to stay alive.

Space Weather

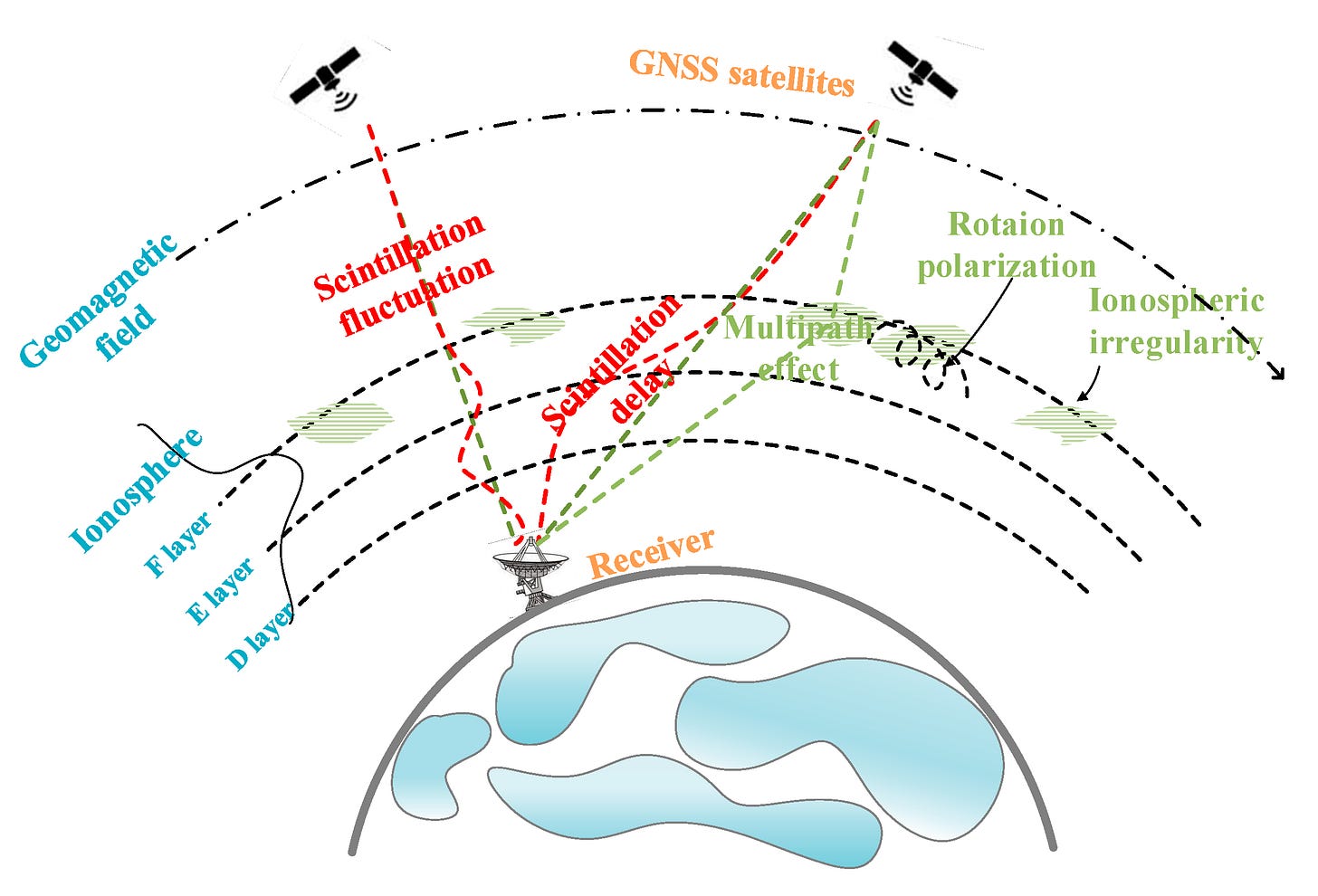

Interestingly, ionospheric scintillation has a large impact on the reliability of GPS around the equator, and this in-turn impacts the reliability of drone flights. This was one of the more challenging problems that we encountered in scaling operations in equatorial countries. Solar radiation creates irregularities in the Earth’s ionosphere, which then causes GPS signals to “scintillate” or fluctuate as they pass through these regions of disturbance. And to make matters more complex, we are currently in the peak period of solar activity in the 11 year Schwabe cycle. Given that Zipline’s core product in equatorial countries is on-demand blood delivery, offered 24 hours / day and relied upon in emergencies, service reliability challenges could not be tolerated.

At the core of many of the solutions we came up with for these challenges was an obsession with testing practical solutions in the field. There are many solutions that sound perfectly reasonable, however in the process of implementation you’re forced to think through every step within a larger system. In doing so, unexpected challenges often reveal themselves that can render a particular solution infeasible. Conversely, a culture of relentless testing can also reveal a path forward through trial and error, that may have at first appeared unlikely to succeed on the whiteboard.

Platform 2

The launch of Zipline’s next generation drone (referred to as “Platform 2”) was the most challenging project that I’ve ever worked on at a startup. I was constantly reminded of this quote from Morris Chang’s early career at Sylvania, where a manager says, “We at Sylvania cannot make what we can sell, and we cannot sell what we can make.” My greatest fear was that perhaps we had envisioned a drone system for Platform 2 that was simply too complex to manufacture affordably at scale. Given that deliveries are now growing steadily in Texas and Arkansas, today Platform 2 appears likely to succeed.

Some of the technical specifications have been publicly shared, and are worth covering here. The drones use dual Nvidia Jetson Orin modules, which enable 275 trillion operations per second. One Nvidia module sits in the mother ship, which hovers ~100 metres above ground, and a second module sits in the delivery droid that descends from the mother ship on tether, to precisely drop an item in a 45cm square. The situational awareness of the drones is quite remarkable, enabling the delivery of delicate goods such as an ice cream cone or cup of coffee to an apartment or a suburban home.

Hardware companies are very odd in some ways, because your success creates massive compounding costs as you scale, which can easily kill the company. As a result, the team has to be extremely talented at financial engineering, meaning you’re constantly raising money and obsessively cutting costs. While a software company might need $2M to reach product-market fit, and $10M to scale; a hardware company, by contrast, might need $10M to produce a proof-of-concept, $50M to scale manufacturing, and $500M for international expansion. This creates an interesting dynamic where the executive team of a hardware startup have to become super talented at raising capital in order for the company to succeed. A great software CEO might tell you that they don’t like speaking to investors, while this is rarely the case with a great hardware CEO. At Zipline, it always felt like we were raising the next financing round before the last financing round had closed, and in retrospect this mindset was critically important for the survival of the company.

In addition, we were maniacally focused on cost reduction, despite raising $1B+ in financing. Everything from supply chain materials to team lunches was carefully monitored for opportunities to cut, and this was deeply embedded in the culture. Over and over, operations and sales teams were drilled with the math required to win:

Revenue x Gross margin - Operating expenses > 0

A culture of frugality and healthy paranoia, never assuming that our survival was guaranteed, enabled our team to persevere while countless competitors slowly perished.

Reducing Maternal Mortality

When I reflect on my time at Zipline, I am most proud of the positive impact we had on local communities. For decades, technologists where doubtful about the potential use cases for drones within healthcare, however the statistics today are overwhelming. Peer reviewed studies in The Lancet Global Health and other leading journals have observed the following outcomes:

56% reduction in maternal mortality at facilities served by Zipline.

67% reduction in blood product expiration at facilities served by Zipline.

71% faster median delivery time for blood products delivered by Zipline.

37 percentage point increase in childhood vaccination rates at facilities served by Zipline.

One of the leading causes of death for women in developing countries is postpartum hemorrhage (excessive bleeding following childbirth), and this is the core problem that Zipline is designed to solve. By centralising storage of blood products in highly sophisticated medical warehouses, and delivering blood units on-demand, Zipline solves the trade-off between access and waste of scarce medical products that plagues healthcare systems in developing countries.

Zipline’s healthcare solution today reaches far beyond emergency blood products. For instance, one of the critical challenges that we sought to solve within vaccine distribution was the prevalence of zero-dose children; 2.25 million children in Nigeria receive no childhood vaccines, and these children account for one-third of all child deaths in the country. In order to solve this, my team structured a partnership with The Global Vaccine Alliance to deliver several million doses of routine immunisations to rural communities over multiple years. This included drone delivery of the RTS,S malaria vaccine, which could prove transformative in combating malaria, a disease that remains one of the leading causes of child mortality globally.

Ultimately, the proof of the solution will be evidenced by the scale of Zipline’s operations. Today, if you take Zipline’s healthcare operations in Africa as a standalone unit, we have surpassed 1 million flights across Rwanda, Ghana, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, and Kenya. While I am confident that we have made a tangible dent in solving the problem of maternal mortality, we still have a long way to go. Over the next 5 years, I envision Zipline operating at national scale across >90% of frontier markets as the backbone of healthcare logistics.