A Short History of the Sphinx of Egypt

Recently, I’ve become interested in the idea that perhaps the generally accepted history of the Sphinx is meaningfully incorrect.

The Great Sphinx of Egypt is conventionally dated to around 2500 BC in the 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu or his son Khafre (i.e. the Sphinx is ~4,500 years old). However, there is no direct evidence that Khufu or Khafre built the Sphinx; instead egyptologists rely on circumstantial evidence, such as the fact that Khufu commissioned other lion-like imagery during his reign, and ancient graffiti inside the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid of Giza directly mentions Khufu. While these data points are noteworthy, they are not compelling evidence that Khufu or Khafre commissioned the Sphinx.

Taking a first principles approach to the problem, we cannot discount the possibility that the Sphinx was potentially built much earlier, e.g. 10,000 to 5,000 BC range (i.e. 12,000 to 7,000 years old), and it was later rediscovered and restored during the Old Kingdom, if the geological evidence steers us in this direction. Specifically, there seems to be evidence of water erosion on the body of Sphinx and the walls of the Sphinx enclosure that point to the statue potentially being significantly older than conventional archeology indicates. The core of this argument is put forward by Robert M. Schoch, an Associate Professor of Natural Sciences at Boston University, in two peer-reviewed articles, Seismic Investigations in the Vicinity of the Great Sphinx of Giza, Egypt (1992, Geoarcheology), and Redating the Great Sphinx of Giza (1992, KMT).

Schoch posits that a geological examination of the erosion on the walls of the Sphinx enclosure reveals telltale signs of persistent rainfall driven erosion over thousands of years, and this is markedly different from the wind driven erosion which is present on many other monuments on the Giza plateau, suggesting that the Sphinx may have been constructed during a different climatic period. Furthermore the limestone blocks on the Sphinx itself were similarly eroded by what appears to be persistent rainfall, and new stones fitted to the eroded blocks behind them. Ancient inscriptions on the stones suggest that the refaced stones dated from the Old Kingdom, which meant that the original walls must have eroded long before that time. Since significant rainfall in Giza is a pre-3000 BC phenomenon, Schoch concludes that the original carving of the Sphinx predates the Old Kingdom by several thousand years.

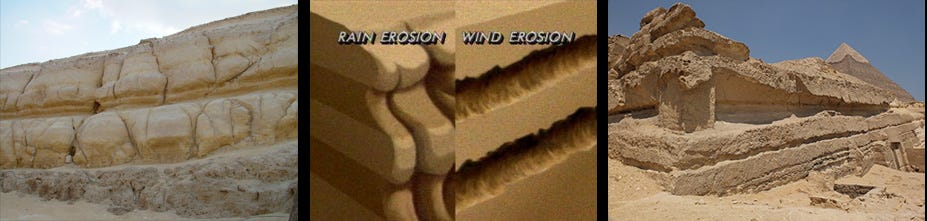

I’m not a trained geologist, but looking at the photos below (left panel is the Sphinx wall, and right panel is a limestone quarry adjacent to the Great Pyramid of Giza), the patterns of erosion are noticeably different.

Left panel: photo of the southern wall of the Sphinx enclosure showing water (via rainfall) erosion.

Center panel: 3D rendering showing the difference between rain versus wind erosion.

Right panel: photo of a limestone quarry adjacent to the The Great Pyramid of Giza, dated by Egyptologists to Old Kingdom times showing only wind erosion.

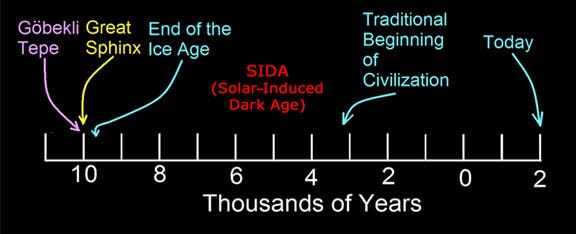

Given this evidence, the below alternative historical timeline suggested by Schoch is at the very least a possibility. So, perhaps the Sphinx was built during an earlier period of lost Egyptian history, only to be forgotten for thousands of years during some kind of climate related dark age, and then rediscovered and restored during the Old Kingdom.

Another fascinating element about the history of the Sphinx is that every few thousand years a new advanced society seems to “rediscover” it largely buried in sand, and is curious enough to re-excavate it.1

For instance, during a short dark period of ancient Egyptian history around 2000 BC, the Giza plateau was abandoned, and sand eventually buried the Sphinx to its shoulders. 500 years later, during the New Kingdom in 1550 BC (18th Dynasty), Pharaoh Thutmose IV, decided to lead an excavation, after a dream in which his father appeared before him in the form of the Sphinx. His court was successful in revealing the paws of the Sphinx, and subsequently erected the granite shrine known as the “Dream Stele” between its paws.

Excerpt from translation of the Dream Stele hieroglyphs,

“O my son Thothmos; I am thy father, Harmakhis-Khopri-Ra-Tum; I bestow upon thee the sovereignty over my domain, the supremacy over the living ... Behold my actual condition that thou mayest protect all my perfect limbs. The sand of the desert whereon I am laid has covered me. Save me, causing all that is in my heart to be executed.”

After the collapse of Egypt’s New Kingdom around 1070 BC, the Giza plateau lost relevance as a holy land, and the Sphinx returned to the sand.

1,000 years later, successive Roman emperors contributed to the restoration of the Sphinx, beginning with Nero in the 1st Century AD. Nero sent an exploratory expedition down the Nile river in 61 AD, and ordered the sand once again cleared from the Sphinx enclosure, followed by the construction of a staircase leading down into the court of the Sphinx. Following this, in 160 AD Marcus Aurelius ordered the restoration of the pavement of the Sphinx court, which was continued by successive roman emperors.

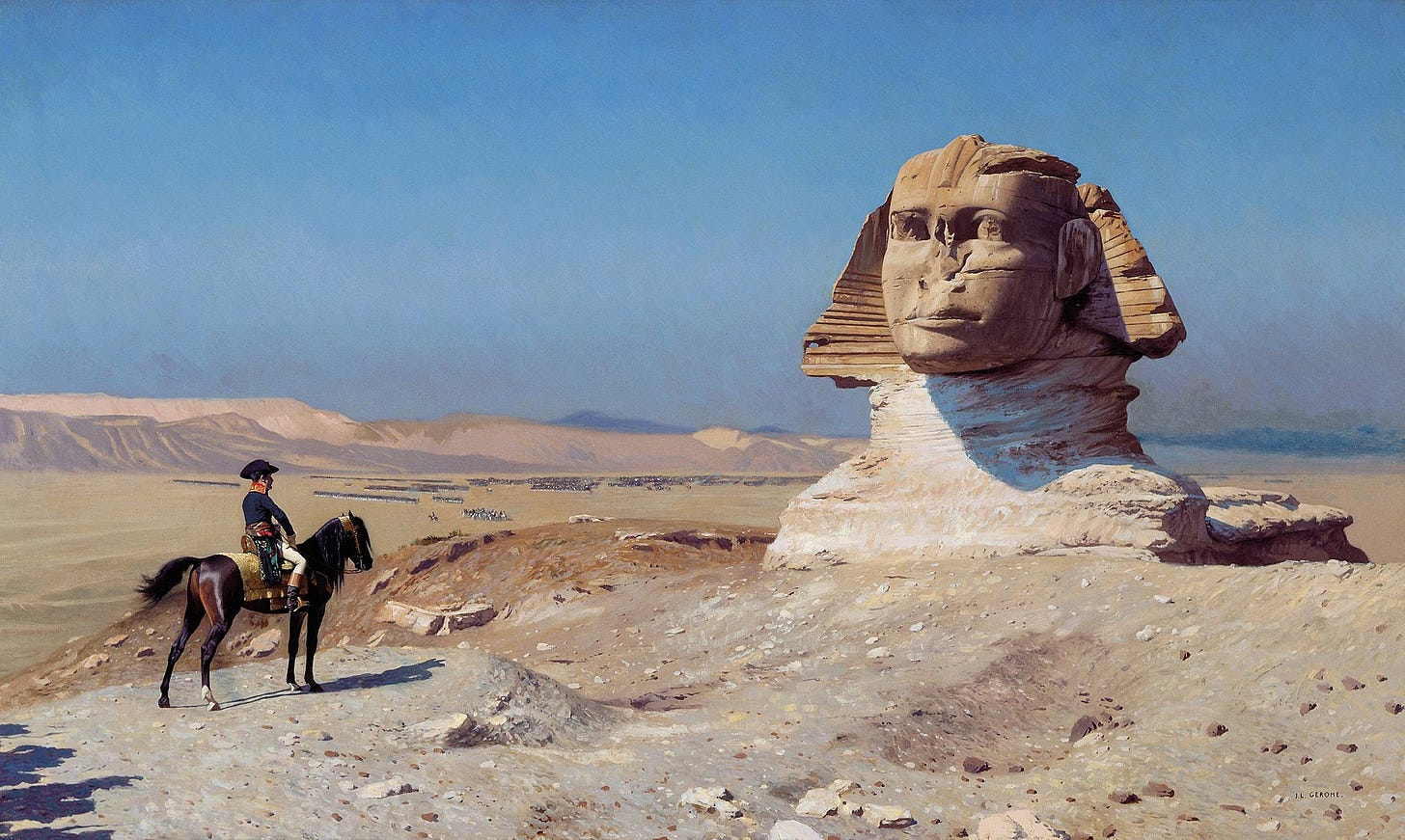

Following ~200 AD, Roman power in Egypt declined, and the desert sands once again claimed the Sphinx, until Napoleon Bonaparte’s military campaign through Egypt ~1,600 years later in 1798. Interestingly, Napoleon travelled with 170 scholars and scientists known as “savants”, and following the trip published The Description de l’Égypte, which sought to comprehensively catalog all aspects of ancient and modern Egypt.

News of Napoleon’s adventures in Egypt led to renewed interest in Egyptology across Europe. 19 years later, in 1817, a British diplomat, Henry Salt, commissioned an Italian explorer, Giovanni Battista Caviglia, to begin a large scale excavation of the Sphinx, the first in modern times. While Caviglia was successful in revealing the chest and paws of the Sphinx, a complete excavation was not completed until 1936, by French egyptologist, Émile Baraize.

So the full body of the Sphinx has only been uncovered for the last 89 years (1936 - 2025). For the vast majority of the Sphinx’s history, following the collapse of whatever civilisation built the monument, it has largely been buried beneath the sand, with only its head revealed; every 1,000 or so years, a new civilisation discovers it, excavates it, and then eventually loses interest or power, at which point the sand reclaims all but the head of the Sphinx. Considering how recently our civilisation excavated the Sphinx from the sands of time, it’s reasonable to consider that we might not yet have discovered its complete history.

Further reading

Robert Schoch, Research Highlights

World History Bulletin, Spring / Summer, 1994

Robert Schoch, The Great Sphinx: She was the Lioness Mehit who Gaurded an Ancient Archive, 2017

Napoleaon Bonapart in Egypt, Epic History, 2025

Howard Vyse, Operations Carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, 1840

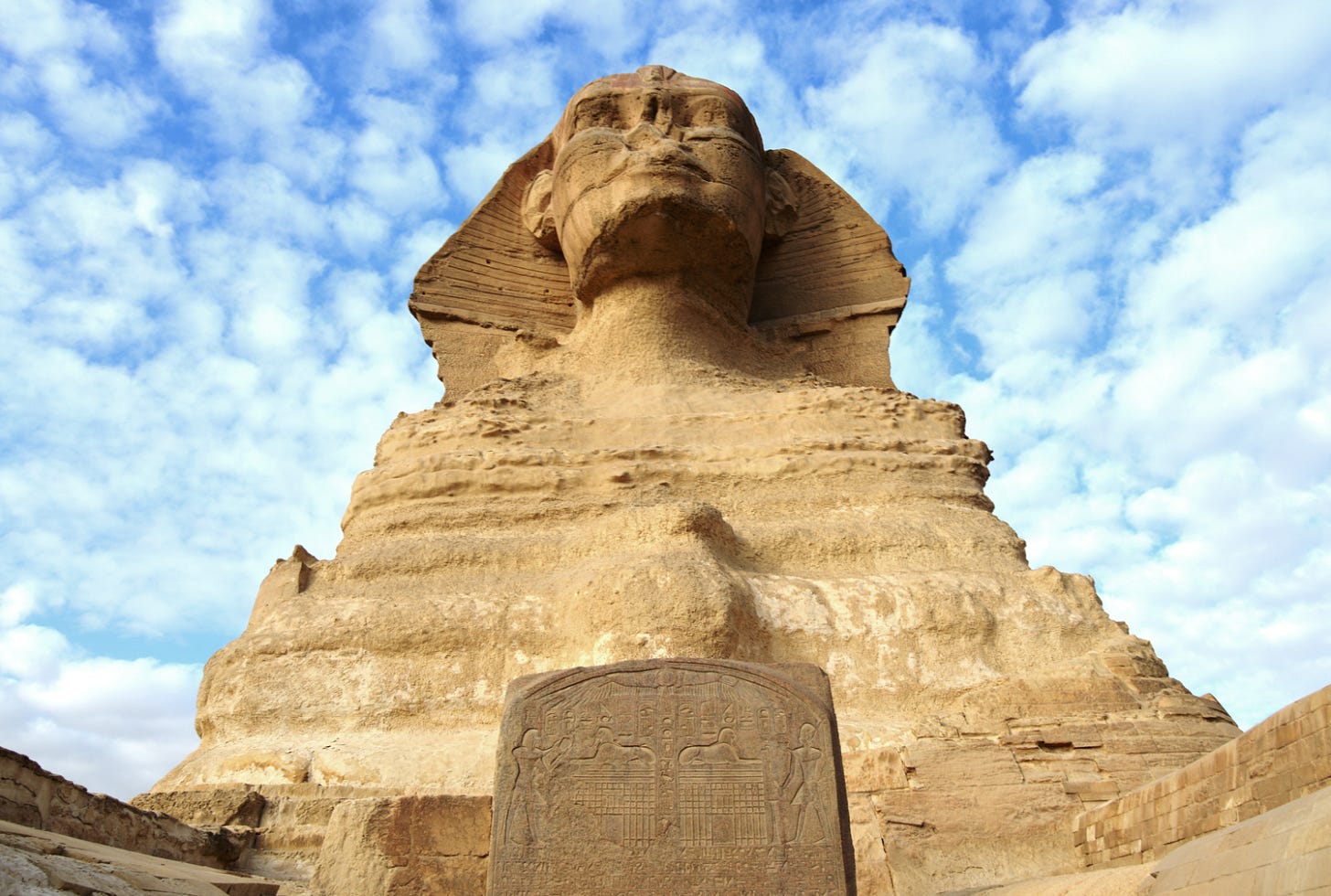

The construction of the Sphinx is somewhat unusual, in that the Sphinx was sculpted out of the limestone bedrock of the Giza plateau, forming a natural quarry around the Sphinx, with only its head visible from outside of the enclosure. Many archeologists and geologists have also noted that the head of the Sphinx is unusual - why does it protrude so far above surface level of the plateau and why is the head noticeably smaller than the body? Some have hypothesised that the head was a natural outcrop of the bedrock that protruded from the plateau, prior to the sculpting of the Sphinx. Another theory is that head has been entirely re-sculpted, and was previously a larger and entirely different face (potentially the head of a lion).